William Henry Holmes woke in the darkness of the pre-dawn farmhouse, his breath visible in the cold bedroom. At 45 years old, his body moved through the ritual of rising – bare feet on the frozen floor, work clothes pulled on in the dark, the long wool underwear and heavy trousers that would keep him warm for the work ahead.

By five o’clock, William Henry had made his way through the snow to the distinctive round barn that stood on his property. The barn was almost new, only 3 years old. Its three stories rose in a perfect circle, topped with a cupola that allowed the building to breathe. The whole structure bore the marks of modern agricultural thinking – efficiency and progressive design. The latest technology for the new 20th century.

The barn’s interior was the geography of daily survival. The cows, in separate stalls, were facing the interior of the circle. The hay could be easily dropped and distributed from the 2nd floor hay loft and middle silo and placed at their heads. The cows were in stalls so that they could be easily hand milked. The perimeter alleyway, with windows, was easily mucked out and kept clean in order to step between each cow. There were pens for calves too and room for at least 2 heavy horses.

William Henry carried a bucket of warm water – he had heated it over the kitchen fire before leaving the house. He wore heavy mittens and kept his hands in his pockets as much as possible, preserving their warmth for the delicate work ahead.

He approached the first cow, Bessie, a Holstein cross. He spoke to her in the low, reassuring tones he had learned years ago. The cow knew his voice, knew the rhythm of their morning together. He positioned himself on the milking stool, a simple 3-legged wooden seat. He washed her udder with warm water, the cow stood still, used to the routine. Then he began to milk, his hands moving in the rhythm he had perfected over two decades. The milk came in long, thin streams, hitting the sides of the clean steel bucket with a sound like rain. The other cows would follow – Daisy, Buttercup, Molly and the others whose names he knew as well as he knew his own children’s.

Henry Farrow, from England, the boy the Holmes family brought with them to Barnston from Bedford, had recently been married and moved to Way’s Mills. So, this year William Henry was a bit short of help in the barn and was missing that extra hand. A few hours of milking lay ahead, working steadily through the predawn darkness, the only light the lantern hanging on a hook, casting long shadows across the circular barn’s interior.

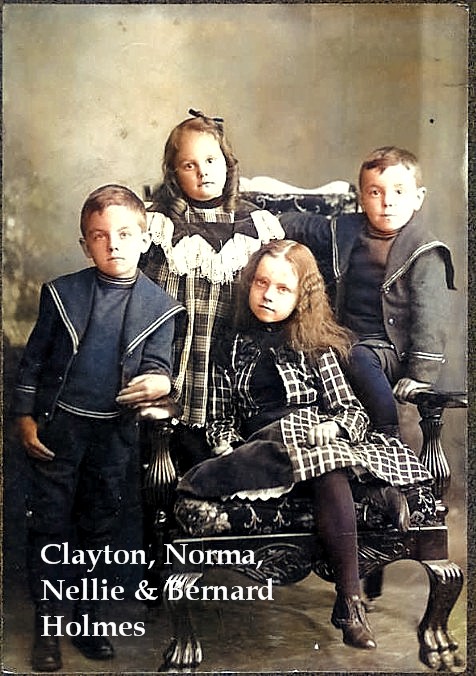

By 6 o’clock, Nellie Eileen, now sixteen, arrived at the barn carrying a bucket of warm water and her own milking stool. She had become skilled enough to handle the morning milking as her father’s equal. Her hands had learned the easy rhythm needed to strip the cows of their extra milk. Her help shaved an hour off the morning routine, and William Henry depended on her completely. Estella normally helped in the barn too, her hands at times became so sore she would soak them in salt water at the end of the day until they became hardened to the routine of stripping the teats.

The boys arrived soon, Clayton and William Bernard – fifteen and thirteen respectively – had their own tasks: feeding the calves and other animals in the barn, breaking ice in the water troughs. Barn cats were waiting for their share of the milking. The horses required oats along with hay to keep them strong and healthy.

By seven-thirty, the morning milking was complete. Perhaps fifteen gallons in all, strained through cheesecloth to remove any straw or dust, then set in the cooling room.

The Farmhouse Comes Alive

Inside, the house smelled of woodsmoke and holiday preparations. Estella Edna had risen early to tend the stove. The wood box was full from the day before, and she raked back the ashes, adding fresh kindling to warm the kitchen.

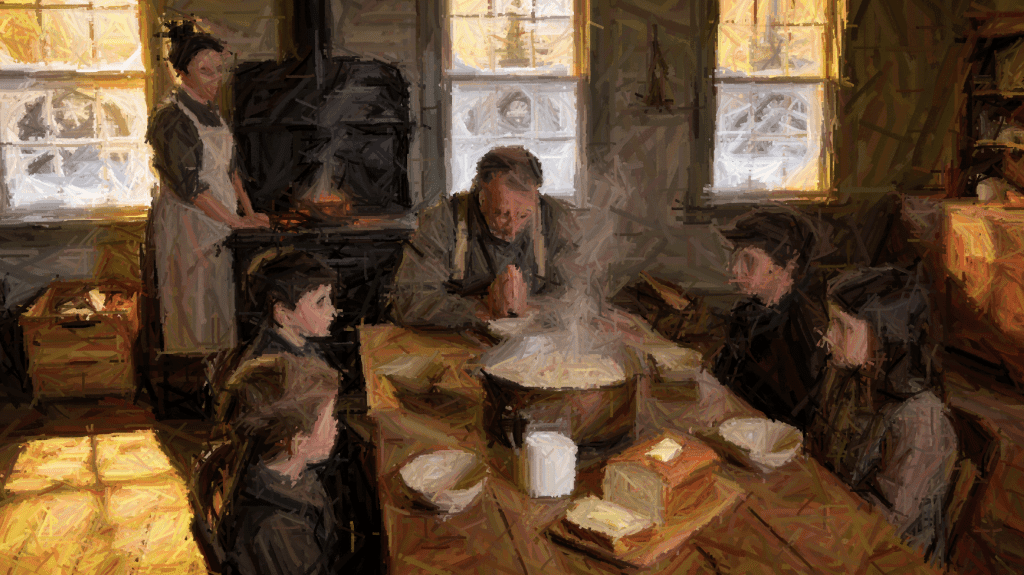

The kitchen was the warmest room in the house, and by eight o’clock the family had gathered there for breakfast. Their meal was plain but sustaining: a great pot of oatmeal porridge that Estella Edna had cooked with butter and salt, served in generous bowls and topped with fresh milk and a little maple syrup added. Alongside it, they ate thick slices of yesterday’s bread with butter and jam put up from the summer fruit.

The meal was eaten with little conversation—the children knew that this was not a time for idle chat. William Henry spoke briefly about the day’s remaining work: the horses must be fed and watered, the pigs needed fresh straw in their pen, the wood supply needed tending. But then, unusually for a farm day, he closed with a brief grace—more than the usual short blessing, acknowledging that this was Christmas, that they were “gathered together in the warmth of home and the provision of the Lord.”

The Journey to Church

By mid morning, the children had changed into their better clothes. For farm families, this meant wool suits that had been pressed carefully and stored away, woolen dresses with collars and cuffs, boots polished clean despite the snow. Estella Edna wore a dark wool coat with a high collar and a hat pinned carefully in her hair.

The horses were harnessed to the cutter—a low, open sleigh with runners that slid easily over the snow. The sleigh bells jingled as William Henry clicked the horses forward, the sound carrying across the frozen valley toward Way’s Mills, where the Union Church stood waiting. The Niger River alongside the road was now locked in ice. The roads were not plowed but “rolled” by horse-drawn rollers to pack the snow down for sleighs. They were adorned with furs or blankets to keep passengers warm against the frosty cold.

The Spiritual centre for the Holmes family was the Union Church, a white clapboard building erected in 1881 that stood directly across the road from the Anglican Church of the Epiphany. They Way’s Mills Union Church Association, united Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, Herald Adventists and Methodists pooling their resources to build a single temple that could serve all their communities.

The Union Church, was already warm with bodies by the time the Holmes family arrived and settled into their customary pew. The Reverend led the service with the same quiet authority that marked rural Protestant worship. The church was heated by a wood stove that created a temperature gradient from roasting heat near its base to near-freezing in the back pews, but no one complained.

The congregation sang the familiar Christmas hymns: Joy to the World, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing, and the relatively new Away in a Manger, which had been popularized in schools and was becoming a favorite among rural families. The Scripture reading was the Nativity story, read without elaboration or dramatic interpretation—just the words from Luke, as they had been read for centuries.

After the service, there was the brief social gathering on the church steps—greetings, news exchanged quickly in the cold, a reminder that despite the isolation of farm life, the community gathered regularly.

Preparing for the Feast

On arriving home again, the boys went out to the barn to complete chores that would simplify the afternoon milking. Before leaving for church, Estella had prepared the goose – raised on the farm and butchered two days earlier – it was rubbed with salt, sage, and thyme, then set to roast in the wood stove for several hours. The kitchen was filled with its rich aroma mixed in with the evergreens. Estella and Norma prepared the vegetables. Turnips were peeled, boiled and mashed with butter. Stored winter squash was scooped and blended with brown sugar and nutmeg. Potatoes were whipped with butter and cream from their own cows.

Estella worked with practiced ease, Norma learned by watching and Nellie moved between rooms, setting the table with the best dishes and a white embroidered cloth sewn by her mother.

The family gathered around the table and the meal began with William Henry’s blessing, brief and heartfelt. Then the food was served: slices of golden, aromatic goose, still steaming; bowls of mashed potatoes; the sweet, soft turnips; the orange-coloured squash; fresh bread with butter melting into its warm interior.

After the savory main course, the dishes were cleared – a task that fell to the older girls while the men and boys remained at the table. Then came the moment that Estella had been planning since September: The Steamed Plum Pudding.

This was not a cake. It was dense, dark, and complex, made with suet (minced beef fat), dried currants and raisins, molasses, spices (cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, and a hint of allspice), breadcrumbs and eggs. The recipe from her own collection handed down by her mother and grandmother through generations of English-speaking families. It had been made four weeks earlier, when the weather was cooling, and it had been stored in a cool place, covered with cloth, aging like wine. The flavors had deepened and married together, the moisture from the fruit seeping through the entire pudding.

Today, the pudding had been removed from its storage, placed in a cloth-lined bowl and set in a larger pot of boiling water – a water bath that would steam it gently for several hours. The slow heat would warm it through completely while maintaining the moisture that made it special.

Estella had also prepared Mince Pies – individual pastries filled with a mixture of minced apple, dried currants and raisins, spices, and a tiny amount of suet. These had been baked in the oven while the main course was served.

When the pudding was ready, it was turned out onto a plate. The hard sauce was prepared: fresh butter whipped with brown sugar until light and fluffy, with perhaps a small splash of brandy or rum whisked in. The Methodists often had strict views on alcohol, but William Henry, with his Irish background, was more moderate in his outlook.

When the pudding was served, it was cut into slices and the sauce spooned lavishly over the top, where it would melt slightly into the warm pudding.

Nellie, sixteen and already thinking about the future, ate her slice thoughtfully. Clayton grinned at the richness of it. William Bernard closed his eyes for a moment, savouring the dark, complex flavors, even Norma, who was usually reserved about sweets, asked for an extra spoonful of sauce.

Gifts and the Eaton’s Dream

After eating, as the snow continued to fall outside the windows and the fire in the stove crackled with a comfortable sound, the family gathered in the parlor for the one moment that all the children had been anticipating: the distribution of gifts.

The decorations in the farmhouse had been simple but meaningful. Greenery – balsam fir boughs cut from the woodlot – hung over the kitchen doorway and the parlor mantelpiece, filling the room with the scent of the forest. It was a smell that meant continuity, heritage, the connection to the land itself. Paper chains that the children had made at school hung across the kitchen window and a single white candle burned in a holder on the table.

The gifts were not placed under a tree – farmhouses rarely had such luxuries – but rather assembled on a table, simple in their wrapping. Each child had a stocking: a cloth bag, sometimes knitted, sometimes simply sewn from heavy fabric. Inside each was an apple from the root cellar, a handful of nuts (walnuts and hazelnuts, cracked open and shelled by Estella Edna in the quiet evenings of November), and a few pieces of hard candy—stick candy in red and white stripes, and barley toys shaped like small animals.

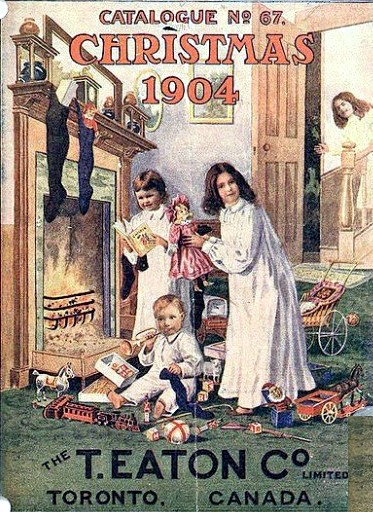

But there was also one “store-bought” item for each child. These were the gifts that had been ordered from the Eaton’s catalogue months ago, discussed and dreamed about through the autumn.

Nellie Eileen received a length of wool fabric—a dark blue wool suitable for a winter skirt. At sixteen, she was approaching womanhood, and this gift recognized that. She would, with her mother’s help, sew it into a simple, practical skirt that she would wear throughout the winter.

Clayton Alfred, fifteen and growing into a young man, received a new pocketknife—a beautiful thing with multiple blades and tools, the kind that a farmer’s son would use for a hundred tasks. He tested each blade carefully, running his thumb along the edge (but not cutting himself; he was careful enough to know better), and his eyes shone with the kind of joy that a new tool brings to a young man.

William Bernard, thirteen, had wanted the tin locomotive with wheels that would roll across the floor. It seemed perhaps childish for a boy his age, but in 1910, toys for teenagers were still simple, and William Henry understood that his son was still caught between boyhood and manhood. The toy was a thing of wonder—it had been shipped all the way from Toronto, manufactured in a factory, painted in bright colors (red and gold, with tiny black wheels). William Bernard wound it up (it had a simple wind-up mechanism) and set it on the floor, where it rolled in a wobbly line across the parlor until it hit the stove leg and stopped. He retrieved it and wound it again, his face alight with satisfaction.

Norma Estella, twelve, received a new dress—not homemade, but actually store-bought, ordered from Eaton’s. It was practical wool, brown with a simple white collar, but it was beautiful to her eyes because it was new, because it had come from the magical catalogue, because it was hers and hers alone.

Shortly after the excitement of gifts, William Henry and the boys headed out to the barn again for the afternoon milking. At this time of the year, it was getting dusky out – the sky was tinged with pink – all was covered with the light snow that created a winter wonderland outside. Inside the barn, the animals were warm and comfortable, waiting for another easy, slow milking. They were all bedded up with fresh straw and made comfy for the chilly night. Lanterns were snuffed out.

The Final Barn Check

Before retiring, William Henry took a lantern and made his way to the round barn. This was a ritual – a final check that all was well, that the animals were settled. The cows were bedded in clean straw, contentedly chewing their cud. The horses were in their stalls, their breath visible in the cold air. Everything was as it should be.

As he walked back toward the house, his lantern casting long shadows across the snow, he could see the lights in the farmhouse windows – oil lamps burning in the bedrooms as his children prepared for sleep. The snow continued to fall, covering the cedar shingles of the round barn, the farmhouse, the snow-packed roads, falling gently on a landscape that had known the Holmes family for thirteen years.

Inside, Estella Edna finished up in the kitchen and climbed the stairs to the cold bedroom where her husband would soon join her. The day was complete—not remarkable in any way that would be noted in a newspaper or remembered in official histories. It was simply Christmas Day on a dairy farm in 1910: a day of work and worship, of family and food, of quiet joy amidst the demands of survival.

The round barn stood in the darkness, its circular silhouette visible against the star-filled sky, a structure that would outlast everyone sleeping beneath the roofs of that farmhouse, a monument to recovery and hope that would stand more than a century into the future.

Epilogue: The Round Barn

The round barn that William Henry and Estella Edna replaced after the devastating fire of 1906 would become one of the most distinctive features of their farm and, eventually, a monument to their resilience. Built in 1907, it represented the most modern agricultural thinking of its era—designed for efficiency, with its circular lay out minimizing wasted steps, its central silo, and its superior ventilation system. When Estella Edna looked out the farmhouse window on Christmas Day 1910, she could see that barn—a three-story cedar-shingled structure with its cupola—as a daily reminder that disaster could be transformed into opportunity.

More than a century later, that barn would still stand, one of the last round barns still in operation in North America, a testament not just to progressive agricultural design but to the determination of a farm family who, in the heart of winter, on a Christmas Day much like any other, continued to milk their cows, prepare their meals, and hold to their faith and their community.

Leave a comment